During the last decade or so I've spent quite a bit of time setting up exhibitions, most of them by artists other than myself. And I have thus also spent a great deal of that time watching people set-up those exhibitions and see them make decisions about how works are placed in the space. This was almost always done with many strong ideas about what a work needs, or what decisions are 'best', and invariably involved a lot of impenetrable minute changes to even smaller details.

Yet in all that time I've never seen anybody actually having some visitors walk through their exhibition in order to observe those visitors and check if all the important adjustments made any difference in how people respond to the works.

This is incredibly odd to me, as some kind of audience testing is done in all other art forms and quite a lot of other industries as well, in the form of quality-assurance. Texts are proof-read, films are screened for test audiences, video games are play tested from very early on in their production and comedians perform try-out shows to see if their jokes get any laughs. This is deemed a necessary and vital step in order to make sure that the thing is actually perceived in the way its meant to be perceived, or sometimes even to make sure it functions at all. Yet this doesn't go for exhibitions. The curator or artist simply make their decisions, decisions they often can't logically justify, and then god saw it was good.

Yet in all that time I've never seen anybody actually having some visitors walk through their exhibition in order to observe those visitors and check if all the important adjustments made any difference in how people respond to the works.

This is incredibly odd to me, as some kind of audience testing is done in all other art forms and quite a lot of other industries as well, in the form of quality-assurance. Texts are proof-read, films are screened for test audiences, video games are play tested from very early on in their production and comedians perform try-out shows to see if their jokes get any laughs. This is deemed a necessary and vital step in order to make sure that the thing is actually perceived in the way its meant to be perceived, or sometimes even to make sure it functions at all. Yet this doesn't go for exhibitions. The curator or artist simply make their decisions, decisions they often can't logically justify, and then god saw it was good.

However I think that in art there is a lot of value to be gained by observing people walk through an exhibition to see how the exhibition functions. Simply noting where people pause, which directions they are facing and how they generally move between the works, gives you a great deal of information. By observing how an audiences behaves there is a lot you can infer about what your audience takes away from the works on display and if they are able to create a cohesive picture in their mind.

In my two years of manning a gallery I've spent quite a bit of time watching people walk through exhibitions and only by watching a bunch of people walk through your shows you can see what is wrong with them. Not only can you see what's wrong with them, in most cases it actually becomes painfully obvious what's wrong with them. Yet curators and artists alike rarely, if ever, test their work, so they are blissfully unaware of how flawed that work really is.

To give a clear example lets look at the posthumous 2022 show of works by Philippe van Snick at the SMAK, Ghent. Co-curator of this exhibition was Luk Lambrecht, who is a very well-respected curator from Belgium. Yet in the exhibition there were some absolute basic mistakes that should and would have been noticed if anybody had actually taken some time to observe people make their way through the exhibition.

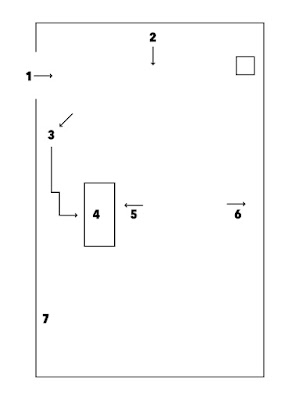

What follows is a photograph and a floorplan of one of the rooms in the exhibition:

During the show there was a forced walking direction through the various rooms, to comply with the covid-19 guidelines that were active at the time. So all visitors entered the space at (1). The most logical choices for works to examine are then (2) and (3). After inspection of (3), the vitrine of (4) is right behind you. So you turn around to look at the various documents in the vitrine, only to find that they are all oriented to be viewed from the position at (5). So in the visitors' most natural path, they first encounter a vitrine full of works in the wrong orientation, which means they have to either walk around or backtrack to able to see the works. Furthermore, if they chose to do this and look at the works in the vitrine, they were then in turn with their backs to the next works at (6) or the vitrine created artificial distance between them and the work at (7).

This is exactly what happened to me when visiting this show and two people right behind me did the same thing, except that they just kept walking to the works at (6) or (7), not even bothering with correcting the mistaken viewpoint and looking at the works in the vitrine at (4).

This anecdote demonstrates a clear shortcoming in the creation of this exhibition that could've easily been fixed if anybody had actually bothered with verifying if their work is functioning as it should, instead of simply assuming it does.